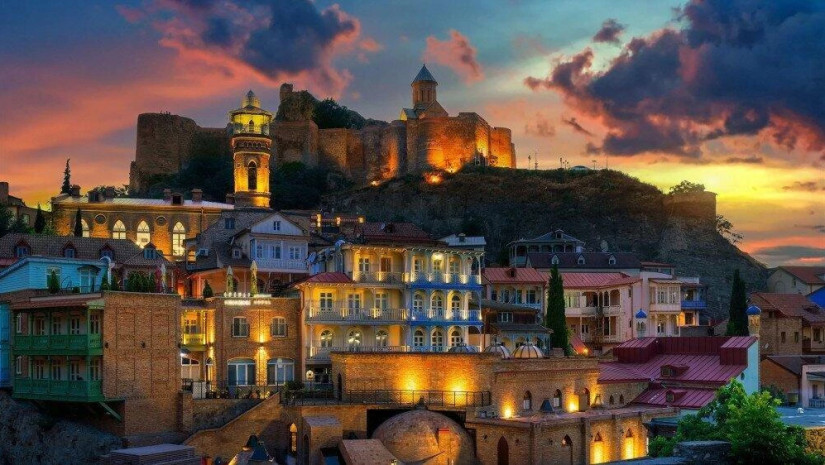

Looking down from the Bridge of Peace, in the center of Tbilisi, the Mtkvari River makes its way east toward the Caspian Sea. Above, there is white metal latticework, and to the side, a glass wall. Visitors seem to float above the city as they cross the bridge. Ahead, a jumbled area of red roofs, trees and winding streets: Tbilisi’s Old Town.

The bridge, designed by Italian architect Michele De Lucchi, opened in 2010. On the banks of the river and in the mountains and valleys beyond, generations of different settlers have traded and fought fierce battles over territory.

The word “bridge” symbolizes unity; these are the foundations of the Bridge of Peace. Georgia and Tbilisi, its capital, are places where different cultures and eras are bridged—and today, Georgian artists, musicians and designers are engaged in their own acts of bridging.

“Tbilisi is very open for everyone. I like that it is a very eclectic city,” says Natalia Vatsadze, one of the founders of Flying Painter, a Georgian art-based clothing brand. “You can find a sixth-century church, castles—and you can find these Soviet constructions and sometimes very ugly buildings. But this mixture of everything, I really love.”

Fabrika is a place that expresses Tbilisi’s eclecticism and energy. The multi-functional cultural center includes cafes and bars, artist studios and shops, educational institutions, co-working spaces and a hostel. On the terrace, visitors can have a drink on the roof of the former Soviet-era sewing factory, which overlooks a 19th-century baroque Catholic church. Tbilisi is not a high-rise city, and from that rooftop it’s possible to see the pattern of its old streets and its fascinating mix of medieval, neoclassical, Beaux Arts, Art Nouveau and moderni buildings. This is just one unique experience offered by Tbilisi’s cultural and historical diversity.

“Tbilisi is very interesting because of this mix of cultures,” says local photographer Louisa Chalatashvili. “And because every part of its history is so clear, every district is very different.”

Before the pandemic, footfall across the Bridge of Peace grew steadily. Tourist numbers in Georgia leapt by 66% between 2013 and 2018, and the annual number of international travelers reached 9.3 million pre-pandemic; Georgia’s population is a mere 3.7 million. The trend looks set continue, with Georgia welcoming 4 million visitors in the first nine months of 2022—a 199% increase on the same period in 2021. Now, the bridge continues to welcome people looking to experience a cultural intersection unlike any other in Europe.

Tbilisi has become a fashionable destination in more ways than one, and in 2017, the influential Fashionista blog declared Georgia “the world’s most exciting fashion destination.” The excitement began with a designer wanting to subvert and disrupt the fashion business. Demna Gvasalia, born in the Georgian city of Sokhumi, started his Vetements collective in 2014, bridging the worlds of the street and the catwalk. The fashion industry evidently liked being subverted: He was named LVMH’s Young Fashion Designer of the Year in 2015, then became creative director of Balenciaga.

Tbilisi’s restless, challenging spirit is alive and well. Head north from the Bridge of Peace towards Egnate Ninoshvili Street, and you’ll encounter the Flying Painter clothing store.

The Flying Painter label was founded in 2016 not by designers, but by artists. Their “wearable art” using high-quality fabrics are clothes that challenge conventional ideas of menswear and womenswear and the throwaway culture of fast fashion. The store itself occupies a converted factory on a pedestrianized street lined with trees and festooned with lights. The environment is as friendly as the service.

“I was 17 or 18, working in this church, and I was looking at these icons, and my wish was born to become an art historian and art critic,” says Vatsadze. Instead, she became an artist, a performer and, ultimately, a designer. She and her fellow artists took over a building stuffed with rolls of fabric, abandoned when the Soviet Union broke apart.

“When we came here, this space was full of boxes with this stuff,” she says. “And they were mostly working with very good materials, whether wool or cotton—all for export. Nothing stayed in Georgia. We cleaned it and now it’s our collection. And what is really cool is that it’s vintage, but also new.”

The Flying Painter name comes from a series of paintings and sketches by Georgian painter and set designer Petre Otskheli. In the 1930s, Otskheli attracted admirers and won awards in the West, but his work was too progressive for Stalin’s cultural overlords. The young artist was arrested and killed in 1937—but the flying painter, his gaze fixed on a better future, lives on.

At night, more feet cross the Peace bridge, now lit up by thousands of LED lights: feet that like to dance. “I’ve been in many clubs in many countries, and I think that we have the best clubs,” declares Tamuna Axander, who runs KHIDI, a club that plays techno and house music over its two floors, with exhibition space on the third floor. “You can see the energy of the people, how they dance, how they are excited to have the night,” says Axander. “The crowd is coming for dancing and for music. Our resident DJ plays 13-, 14-hour sets.”

In the summer season it becomes Georgia’s “second capital”, with a lively arts and music scene, and Asian-influenced cuisine. The Batumi renaissance is well under way: in the October 2022 World Travel Awards it was named Europe’s fastest growing tourism destination.

It’s also in Batumi that you’ll encounter one of Georgia’s most poignant cultural landmarks.

Tamara Kvesitadze’s “Ali and Nino” is a public kinetic sculpture of a male figure and a female figure who, once a day, approach, embrace and seemingly pass through one another before separating. Originally named “Man and Woman,” it was renamed in 2010 after the characters in the famously tragic 1937 novel about a Muslim boy and an Orthodox Christian princess. The work tells a tale from the past—but in the new, culturally diverse Georgia, maybe Ali and Nino really do live happily ever after.

Source: Bloomberg