This Article was first published by The National Interest.

Georgia has successfully dealt with the coronavirus outbreak but now must meet the task of conducting free, fair, and transparent parliamentary elections on October 31 and dealing with the economic impacts of the pandemic. Each of us has served as U.S. Ambassador to Georgia and can attest that the country has come a long way in democratic and economic reforms since independence in 1991. We were encouraged by the compromise electoral reform law adopted earlier in the year, but the whole election process could be reformed to better reflect the will of the Georgian people.

There is serious concern over Russian interference in the upcoming election. U.S. Ambassador to Georgia Kelly Degnan has twice warned that “Georgians should expect that Russia is going to interfere” based on “a long pattern of interference through disinformation campaigns and other efforts.’’

Many of Georgia’s friends abroad have been uneasy about the country’s recent reform trajectory. This is illustrated by a recent House Appropriations Committee proposal to block 15 percent of U.S. aid unless Tbilisi “strengthens democratic institutions,” does more to fight corruption and protects foreign businesses operating in Georgia. This proposal may not survive the legislative process, but it is a signal that the upcoming election and Georgia’s dealings with foreign investors will be carefully monitored.

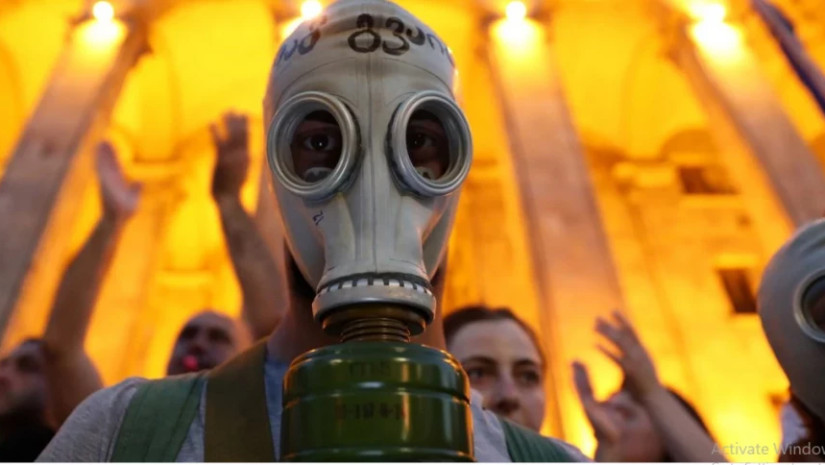

The run-up to the 2018 presidential election was “marked by violence and intimidation” and threats against foreign nongovernmental organizations. In June 2019, rubber bullets and tear gas were used “without warning against thousands of nonviolent protestors” outside the Parliament.

A December 2019 National Democratic Institute (NDI) poll found that 53 percent of Georgians thought the country was going in the wrong direction and only 19 percent in the right direction. The same poll showed that 59 percent of respondents did not believe Georgia was a democracy, a jump from 46 percent one year before.

Earlier this year, polarization between the government and opposition over the terms of the electoral law for the upcoming parliamentary election reached worrisome levels. To Georgia’s credit, the parliament, with mediation by the U.S. and European ambassadors, approved a compromise in March under which 120 seats will be allocated on the basis of proportional representation and thirty by majoritarian voting. This and the lowering of the electoral threshold for parties to gain seats seem like fair solutions. A helpful step in the negotiations was the pardoning of Gigi Ugulava, leader of the European Georgia-Movement for Freedom party, and Irakli Okruashvili, leader of the Victorious Georgia party.

The election campaign has now kicked off but there are complaints. Reporters without Borders has voiced concern that the “climate is becoming oppressive for Georgia’s media” as a result of judicial harassment and tightened legislation, and rushed amendments to a communications law “evince a clear desire to control radio stations and TV channels.”

Georgia’s friends and neighbors are carefully watching the runup to the election and will pay close attention to the voting. They will assess media freedom and access, integrity at polling stations and vote counting, and any use of instruments of government power by Georgia Dream to gain unfair advantage. The conclusions of independent domestic and international observers will influence perceptions.

Georgia hopefully can build on its success in dealing with the coronavirus. From the beginning, the government listened to scientists and public health experts and moved quickly with quarantining, testing, wearing masks, and blocking entrance to foreign travelers. Deaths so far are limited to nineteen and restrictions are being lifted in a careful and measured way. An NDI poll conducted last July shows the overwhelming majority of Georgians credit the government and public health experts with managing the crisis effectively and turn to them for reliable information.

The economic scene, however, is less positive. The coronavirus hit the economy hard, with a GDP decline of about 5.5 percent this year predicted by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. Previous annual growth rates this decade averaged about 4-5 percent. Unemployment remains an Achilles heel and poverty rates are still high, especially in rural areas.

The emergency steps taken by the government to shore up the economy have helped but there is an urgent need for more foreign investment. Restrictive land ownership laws, flaws in dispute settlement mechanisms, and shortcomings in the rule of law remain obstacles, even as Georgia has cleaned up much petty corruption and made significant progress in implementing transparency measures for doing business. Georgia ranks seventh globally in the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business 2020 study.

Two red flags have recently gone up for foreign investors. A private Georgian-led consortium won a government tender to build a Black Sea deep-water port in Anaklia costing some $2.5 billion. Aimed at container shipping, the port could advance Georgia as a major Asia-Europe commercial entrepot. The stalled project seems to have become politicized and the government is unwilling or unable to provide sufficient backing and sovereign guarantees to satisfy international lenders. A U.S. partner was involved but appears to have pulled out.

The second project involves an international consortium that seeks to assemble a fiber-optic communications network, a “Digital Silk Road,” which would connect Europe via the Black Sea, the South Caucasus and Central Asia. The consortium purchased 49 percent of a Georgian telecom company to secure an important asset. The Georgian government through the amended communications law may try to reverse the purchase or even seize the asset.

In both cases, there is a risk the companies will take the Georgian government to international arbitration (which may now be happening with Anaklia). This could frighten off some potential foreign investors. Negotiated settlements could reduce these risks.

Over the past three decades, Georgia has faced wars and daunting challenges to its sovereignty, democratic development, and economic growth. We have every confidence it can meet these latest tests as well.

Kenneth Yalowitz is a Global Fellow at the Wilson Center and an adjunct professor at Georgetown University, and former U.S. Ambassador to Belarus and Georgia.

John Tefft is an adjunct senior fellow at the nonprofit, nonpartisan RAND Corporation and a former U.S. Ambassador to Lithuania, Georgia, Ukraine, and Russia.

William Courtney is an adjunct senior fellow at RAND and a former U.S. Ambassador to Kazakhstan, Georgia, and a U.S.-Soviet commission to implement the Threshold Test Ban Treaty.